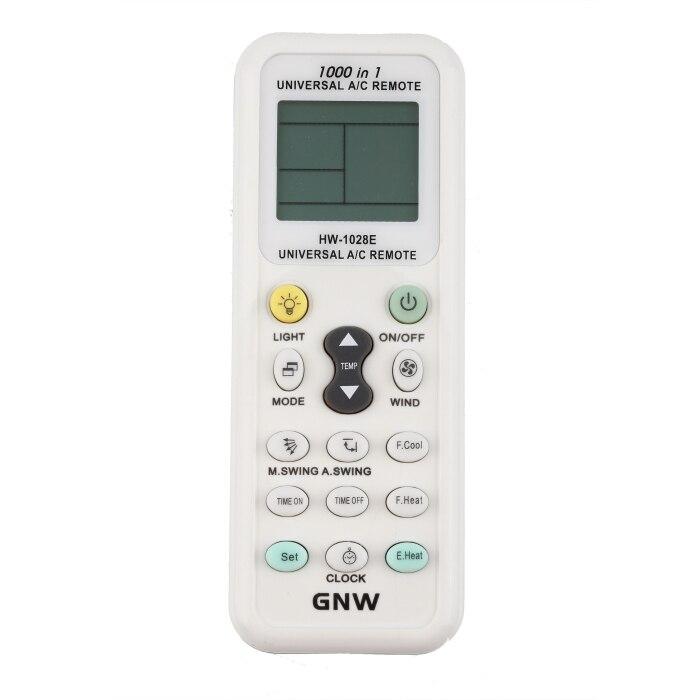

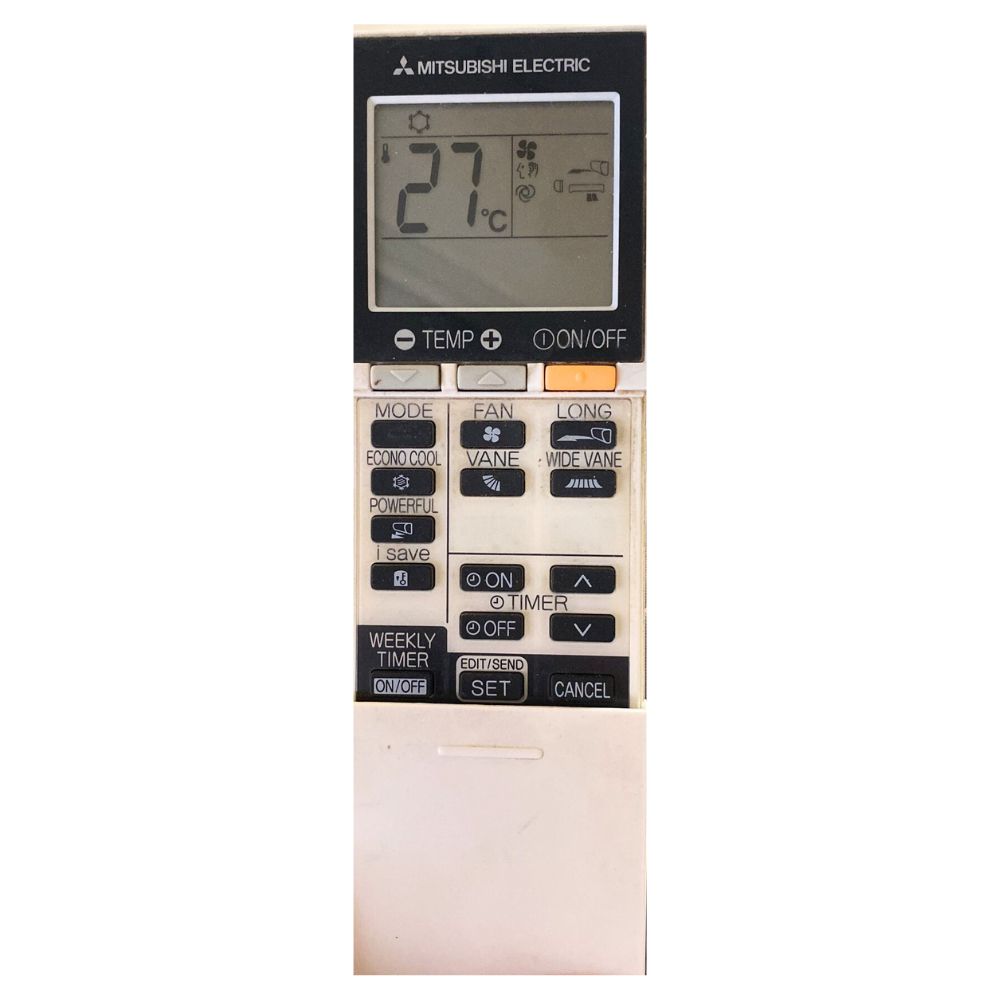

Amazon.com: אוניברסלי מזגן שלט רחוק LCD A/C מיזוג בקר 1000 ב 1 עבור מיצובישי טושיבה HITACHI FUJITSU דייהו LG שארפ סמסונג אלקטרולוקס SANYO AUX GREE HAIER Huawei מיזוג אוויר : לבית ולמטבח

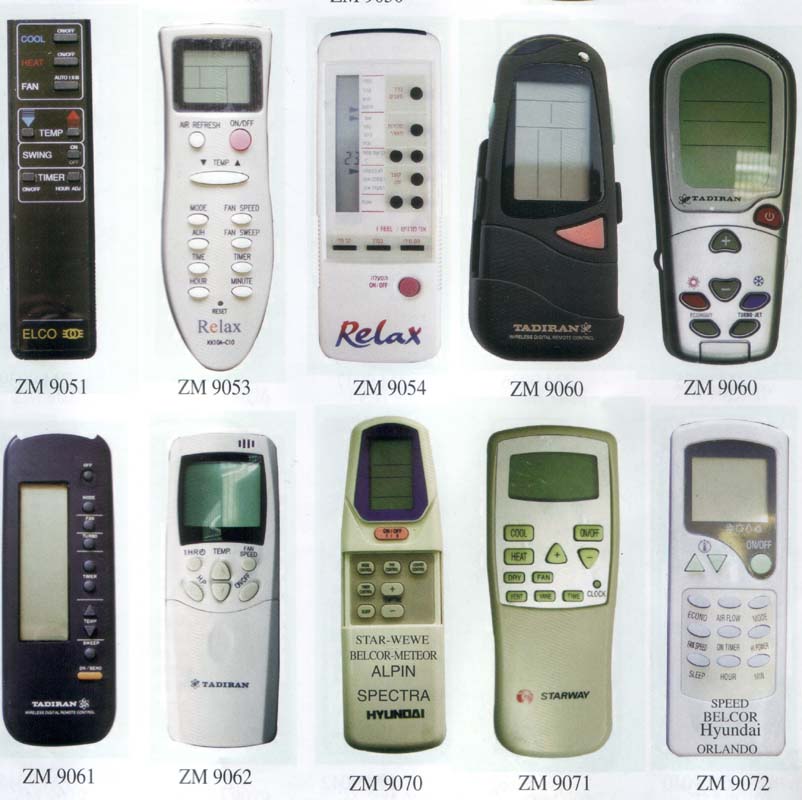

שלט אוניברסלי למזגני אלקטרה אלקו 23 שלטים בשלט בודד USP-4008 USP-4006 שלט רחוק למזגנים USP4008 USP4006 שלט למזגן מקורי אוניברסלי ELECTRA | שלט אלקו | שלט אלקטרה